by Joanna Dawson

On the first days of April, 1914, crowds of people gathered around the telegraph office in St. John’s Newfoundland. Word was coming through about the greatest marine disaster in the nation’s history. Mothers, wives and children were anxious to find out if their loved ones would be among the few lucky survivors or among the unfortunate souls who perished at the hand of the frigid North Atlantic.

On the first days of April, 1914, crowds of people gathered around the telegraph office in St. John’s Newfoundland. Word was coming through about the greatest marine disaster in the nation’s history. Mothers, wives and children were anxious to find out if their loved ones would be among the few lucky survivors or among the unfortunate souls who perished at the hand of the frigid North Atlantic.

What’s now known as the 1914 Sealing Disaster refers to two separate, simultaneous tragedies on the sea in the spring of 1914. The SS Southern Cross and SS Newfoundland suffered a combined loss of 251 men, leaving hardly any person or community unaffected by the events.

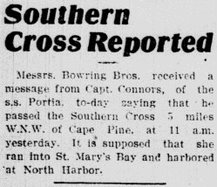

The Southern Cross was returning from a successful hunt and was on track to be the first ship to return to port that year. She was spotted as she sailed by Cape Ray on the south west coast of the island and again by the SS Portia near St. Mary’s Bay. All reported that the Southern Cross was sailing with all flags flying — a sign that she had a full cargo and was returning home.

But the men on the Southern Cross never had a chance to boast about their successful hunt. The ship inexplicably sank, taking all 174 men to their watery graves. Without any surviving witnesses, wireless communication, or ship logs, little is known about the Southern Cross. The official verdict was that the ship sank in the blizzard of March 31, but theories that the ship’s heavy cargo contributed to the accident were prevalent.

But the men on the Southern Cross never had a chance to boast about their successful hunt. The ship inexplicably sank, taking all 174 men to their watery graves. Without any surviving witnesses, wireless communication, or ship logs, little is known about the Southern Cross. The official verdict was that the ship sank in the blizzard of March 31, but theories that the ship’s heavy cargo contributed to the accident were prevalent.

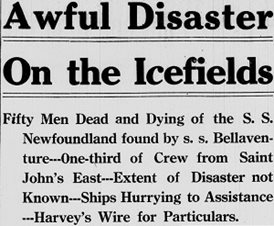

At the same time, a horrific, sad, and preventable tragedy was unfolding for the men of the SS Newfoundland. The Newfoundland was one of the smaller ships in the 1914 fleet – without a strong icebreaker it was immediately at a disadvantage. However, the ship’s captain, young Captain Westbury Kean came from good lineage – his father was the famed mariner Captain Abram Kean of the SS Stephano. Although the father and son were working for competing companies, they had arranged a discrete signalling system so that one could notify the other when he came across a group of seals.

And so when Captain Abram raised his derrick on March 30th, only his son knew that he had found a good patch of seals. Unable to cut through the thick ice, the captain of the Newfoundland ordered his men to make their way to the Stephano by foot.

The men followed orders and set out around 7:00am. Sensing foul weather on the horizon, a few of the men headed back to their ship a few hours into the journey. The rest of the group forged ahead through some of the toughest ice they had ever seen. It was over four hours later when they finally boarded the Stephano. After a quick cup of tea and some hard tack, Captain Abram Kean ordered the men back onto the ice for a killing.

Captain Abram sailed the ship to where he thought he saw a patch a seals closer to the Newfoundland – however, he misjudged the direction and ended up leaving the sealers off course and further away from their own ship than they thought. The men walked for some time looking for seals, but soon abandoned the hunt and tried to return to their ship.

But the men were exhausted and disoriented, and the harsh weather prevented them from finding the Newfoundland. Sadly, the Newfoundland had no wireless machine — the ship’s owners had removed it the previous week because it seemed an unnecessary expense. With no means of communication, both captains presumed that the men were safe aboard the other’s ship . Neither sent out a search or even sounded the ship’s whistle through the night. One hundred and thirty two sealers were stranded on the ice for two nights. By the time the men were rescued, 77 had perished from the cold.

An inquiry into the disaster was held in 1915. Although nobody was held legally responsible, the captains of the Newfoundland and Stephano, as well as George Tuff — the officer in charge of the sealers on the ice — were all found guilty of errors in judgement. The commission recommended that all ships must carry wireless sets, barometers, and thermometers. In response to the tragedy of the Southern Cross, legislation was passed to prohibit vessels from carrying more than 35,000 pelts. Family members could take some comfort knowing that conditions would be better and safer for future sealers.

One of the Master Watches of the Newfoundland, Thomas Dawson, was my grandfather’s cousin. “Skipper Tom,” as he was called led the sealers on the ice for much of the time, breaking the path through the hard snow for the others. When he lay down to sleep on the second night, the other men assumed that would be the end of Skipper Tom. But one of the sealers stacked the bodies of the perished men around Tom while he slept and he miraculously survived the night. He suffered badly from frostbite and was unable to stand or walk by the time the men were discovered. His legs were amputated and he relied on prosthetics for the rest of his life.

On the 100th anniversary of the 1914 sealing disaster approaches, many Newfoundlanders reflected on the lives lost and lessons learned. The Elliston Heritage Foundation launched a campaign to create an interpretive centre to commemorate all the sealers about the Newfoundland and Southern Cross. A memorial statue, created by Morgan MacDonald, depicts the true story of a father and son who were found frozen in an embrace. It’s a haunting image, but one we must remember to honour all those affected by this tragic event.

Website:

Heritage Newfoundland & Labrador

Article:

Books:

Death on the Ice, by Cassie Brown

Perished: The 1914 Newfoundland Seal Hunt Disaster, by Jennifer Higgins

Left to Die: The Story of the SS Newfoundland Sealing Disaster, by Gary Collins

Death On Two Fronts, by Sean Cadigan

Videos:

Caught Out In A Storm, Land and Sea (original air date May, 2009)

54 Hours (National Film Board)